Science Corporation’s retinal implant has enabled some individuals who have lost their central vision to engage in activities like reading, playing cards, and recognizing faces.

Losing Central Vision

For years, these individuals experienced a gradual loss of central vision, which is crucial for seeing details, faces, and letters clearly. The deterioration of light-receiving cells in their eyes was slowly blurring their sight.

Experimental Eye Implant

However, after participating in a clinical trial and receiving an experimental eye implant, some participants can now see well enough to perform tasks like reading, playing cards, and completing crossword puzzles despite being legally blind. Science Corporation, a California-based brain-computer interface company, announced these preliminary results this week.

Max Hodak, CEO of Science and former president of Neuralink, was astounded when he first saw a video of a blind patient reading with the aid of the implant. This led his company, which he founded in 2021 after leaving Neuralink, to acquire the technology from Pixium Vision earlier this year.

“I don’t think anybody in the field has seen videos like that before,” he says.

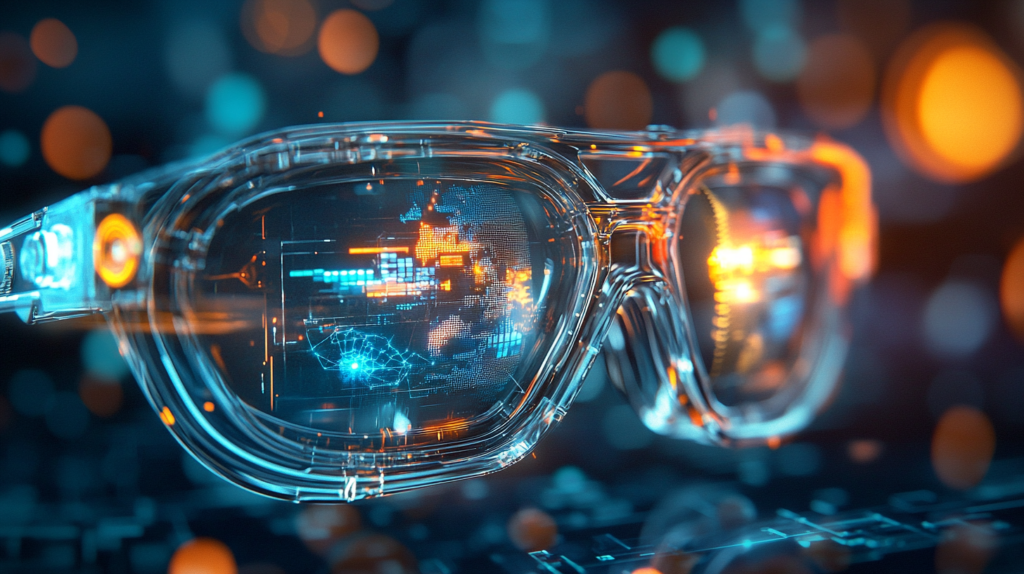

The Prima Implant

Called the Prima, the implant consists of a 2-mm square chip that is surgically placed under the retina, the backmost part of the eye, in an 80-minute procedure. A pair of glasses with a camera captures visual information and projects patterns of infrared light onto the chip, which contains 378 light-powered pixels. Acting like a tiny solar panel, the chip converts light into electrical stimulation patterns and sends those pulses to the brain. The brain then interprets these signals as images, mimicking the process of natural vision.

Previous Attempts

There have been other efforts to restore vision by electrically stimulating the retina. These devices have been able to generate spots of light known as phosphenes in people’s field of view, similar to blips on a radar screen. While these are sufficient to help people perceive people and objects as white dots, they fall short of providing natural vision.

One such device, the Argus II, was approved for commercial use in Europe in 2011 and in the US in 2013. This implant involved larger electrodes placed on top of the retina. Its manufacturer, Second Sight, ceased production in 2020 due to financial difficulties. Meanwhile, companies like Neuralink are exploring ways to bypass the eye entirely by directly stimulating the brain’s visual cortex.

Form Vision

Hodak says the Prima differs from other retinal implants in its ability to provide “form vision,” or the perception of shapes, patterns, and other visual elements of objects. However, the vision users experience isn’t “normal” vision. They don’t see in color but rather see a processed image with a yellowish tint.

The trial enrolled people with geographic atrophy, an advanced form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) that leads to a gradual loss of central vision. Individuals with this condition retain peripheral vision but have blind spots in their central vision, making it difficult to read, recognize faces, or see in low light.

In AMD, specialized cells called photoreceptors, located at the back of the retina, are damaged over time. These cells convert light into signals that are sent to the brain. “The photoreceptors are lost, but the retina is preserved to a large extent. In our approach, the implant takes the place of the photoreceptors,” says Daniel Palanker, a professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University, who invented the Prima implant.

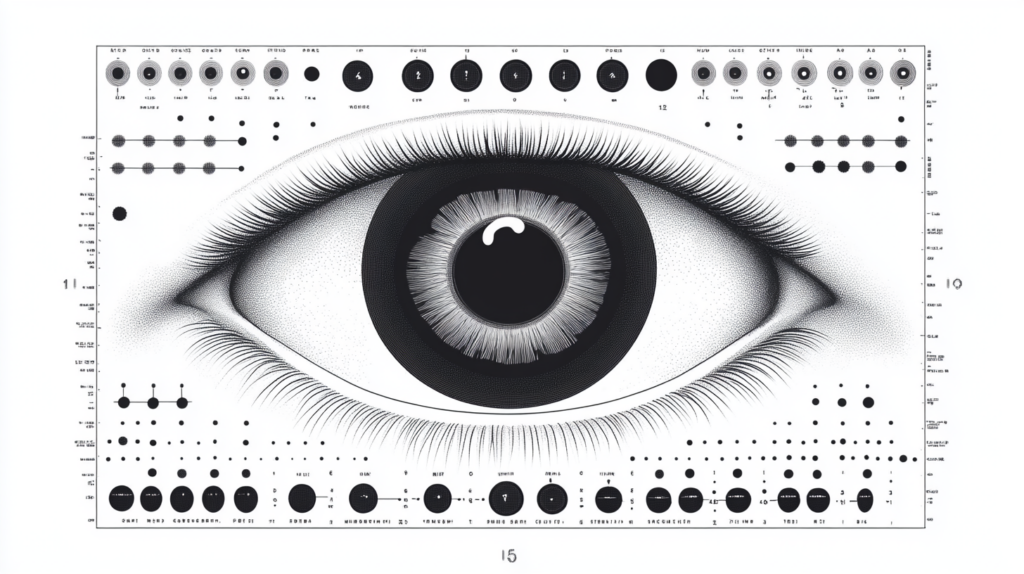

Study Results

The trial initially enrolled 38 participants aged 60 and older in the UK and Europe, but six dropped out before the one-year mark. To measure improvement in vision acuity, researchers used a classic eye chart. Participants started with an average visual acuity of 20/450. Normal visual acuity is considered to be 20/20, and in the US, legal blindness is defined as 20/200 or worse.

After a year, the 32 people who remained in the trial were able to read nearly five more lines on the vision chart, or an average of 23 letters, compared to their baseline. This improved their eyesight to an average of 20/160. Palanker says some participants can even see at 20/63 acuity using the implant’s zoom and magnification feature. However, while most participants saw a notable improvement, five did not benefit at all.

“The results are very impressive,” says James Weiland, a biomedical engineer and ophthalmologist at the University of Michigan, who wasn’t involved in the study. He notes, though, that the preliminary data doesn’t specify whether participants were using the zoom feature during the vision tasks. He says this matters because manually activating the zoom function makes the process of seeing with the implant less natural.

“It’s a step forward for retinal prostheses, for sure. But there are some details we don’t know that could tell us how big of a step it is,” Weiland says. “And one of those details is whether the patients were using a magnified image when they recognized these letters.”

A spokesperson for Science Corporation says participants have the option to use the zoom feature as needed but didn’t provide details on how often it was used during the study period.

The Need for Vision Restoration

“Of the various chip implant technologies that have been tried over time, this is the one that seems like it has some potential,” says Sunir Garg, an ophthalmologist at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia and a clinical spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology, who wasn’t involved with the Prima study. “What we don’t know yet is how useful it will be in day-to-day functioning for people.”

Garg highlights the significant need for such devices because AMD is the leading cause of vision impairment in older individuals. In the US alone, an estimated 20 million Americans have AMD, and the global number of affected individuals is expected to rise significantly over the next 20 years. “Once that central vision goes bad,” Garg says, “we don’t have any ways to make it better.”